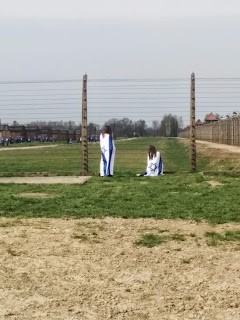

Several years ago I returned from a mission to Poland and Israel. At the time, our group was left with one inescapable conclusion: Jewish History is a rollercoaster of horror and happiness. In Poland we saw piles of human hair and cans of zyklon-b pellets. In Israel we saw smiling schoolchildren and maternity wards . In Poland we saw cattle cars. In Israel we saw proud soldiers. In Poland we saw gas chambers. In Israel we saw new construction. Up close, Jewish History becomes an emotionally turbulent experience.

The Israeli calendar is even more chaotic. The day before Independence Day is Memorial Day. Unlike the United States and Canada, in Israel Memorial Day is quite melancholy. Everyone attends a memorial, and the entire country stops when the siren rings. When I asked our security guard, Amit, to say a few words about Memorial Day, he choked up with tears; he had served in a combat unit and had lost friends in battle.

And then, immediately after this comes absolute celebration. As if by the flick of switch, the entire country is transformed into a one big block party, with revelers roaming the streets and families barbecuing in the park. In a uniquely Jewish fashion, we insist on commemorating tragedy immediately before celebrating independence. (Much like the Passover Seder includes mention of both slavery and freedom).

This Jewish need to combine bitter and the sweet memories together is what lies at the heart of an authentic Jewish historiography. Jewish history consists of both exile and redemption. We don’t view exile as meaningless historical time, something we’d prefer to forget. On the contrary, exile is carefully remembered. And this is the paradox of Jewish History: it sees exile and redemption, seeming polar opposites, as deeply connected experiences. And like all good paradoxes, it is meant to be a question that keeps asking questions.

This paradox teaches multiple lessons. It underlines the fact that Israel (and the Jewish people) continue to survive and thrive, despite our challenges. It reminds us that the manifold miracles of contemporary Israel, such as blooming deserts, the return to the Western Wall, and cutting edge medical research are expensive miracles; over 23,000 soldiers paid with their lives for these achievements. And it teaches us that we must continue to claim the moral high ground, and refuse to descend to the level of the terrorists who attack us.

At the end of Memorial Day, I was at a ceremony in which the Israeli flag, flying at half mast, was raised to full height. At that moment, I understood I was experiencing all of Jewish history in two minutes. Jewish history lives at the intersection of exile and redemption, the point of transition between half mast and full glory. It may seem an absurd way to look at history; but wasn’t it also absurd for this small, persecuted people to persist in living on?

The Israeli calendar is even more chaotic. The day before Independence Day is Memorial Day. Unlike the United States and Canada, in Israel Memorial Day is quite melancholy. Everyone attends a memorial, and the entire country stops when the siren rings. When I asked our security guard, Amit, to say a few words about Memorial Day, he choked up with tears; he had served in a combat unit and had lost friends in battle.

And then, immediately after this comes absolute celebration. As if by the flick of switch, the entire country is transformed into a one big block party, with revelers roaming the streets and families barbecuing in the park. In a uniquely Jewish fashion, we insist on commemorating tragedy immediately before celebrating independence. (Much like the Passover Seder includes mention of both slavery and freedom).

This Jewish need to combine bitter and the sweet memories together is what lies at the heart of an authentic Jewish historiography. Jewish history consists of both exile and redemption. We don’t view exile as meaningless historical time, something we’d prefer to forget. On the contrary, exile is carefully remembered. And this is the paradox of Jewish History: it sees exile and redemption, seeming polar opposites, as deeply connected experiences. And like all good paradoxes, it is meant to be a question that keeps asking questions.

This paradox teaches multiple lessons. It underlines the fact that Israel (and the Jewish people) continue to survive and thrive, despite our challenges. It reminds us that the manifold miracles of contemporary Israel, such as blooming deserts, the return to the Western Wall, and cutting edge medical research are expensive miracles; over 23,000 soldiers paid with their lives for these achievements. And it teaches us that we must continue to claim the moral high ground, and refuse to descend to the level of the terrorists who attack us.

At the end of Memorial Day, I was at a ceremony in which the Israeli flag, flying at half mast, was raised to full height. At that moment, I understood I was experiencing all of Jewish history in two minutes. Jewish history lives at the intersection of exile and redemption, the point of transition between half mast and full glory. It may seem an absurd way to look at history; but wasn’t it also absurd for this small, persecuted people to persist in living on?

Happy 68th, Israel!