Parsha Inspiration - "Who Are You Dreaming For?"

Thank you again to Lorne Lieberman for sponsoring the Video, and Jacob Aspler for the video work.

Happy Chanukah!!

Friday, December 19, 2008

Saturday, December 13, 2008

Parsha Inspiration - "Tragedy is a Comma, Not a Conclusion"

Third installment of this new project - a point of inspiration on the parsha or current events, captured on video for youtube.

A huge thank you to Lorne Lieberman for chasing me for 2 years to do this, and Jacob Aspler for doing the video.

Please send me your comments and thoughts on this.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wYsNG4U4Mlw

Third installment of this new project - a point of inspiration on the parsha or current events, captured on video for youtube.

A huge thank you to Lorne Lieberman for chasing me for 2 years to do this, and Jacob Aspler for doing the video.

Please send me your comments and thoughts on this.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wYsNG4U4Mlw

Tuesday, December 09, 2008

Where is the Jewish Community?

It was a moment of Jewish inspiration. A thousand Montreal Jews huddled together in a synagogue to conduct a memorial service for the victims of the Mumbai massacre and the Mumbai Chabad House. Every type of Jew, including Satmar, Lubavitcher and Belzer Chassidim, Reform, Conservative, Orthodox, Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews, all came to the memorial. It was a powerful display of Jewish unity.

But after the inspiration, I was left with disappointment. The evening of course was touching and meaningful, but I was left with a nagging doubt: would this unity last? Yes, we Jews come together when things are difficult. Much like the old saying that “there are no atheists in foxholes”, there are no quarrels during tragedies; disasters have the unique ability to unite Jews together in a common cause. Bloodshed brings Jews together.

But when things get a little more comfortable, our unity fades. During the difficult days at the beginning of the Intifada, thousands of Jews, shocked by the images they saw on their TV screens, came out to rallies in support of the State of Israel. It was a critical juncture, a time “when the chips were down”, and even ultra-Orthodox Jews who wouldn’t consider themselves “Zionists” came to support the Jewish State. But once the violence quieted down, people were less willing to give their active support to Israel. Jewish unity is much more difficult to achieve in good times.

In difficult times, our hearts are touched by another person’s suffering. This powerful emotion, empathy, can affect even the most evil of human beings. While murdering six million other Jews, Adolf Hitler went out of his way to spare the life of his mother’s Jewish Doctor, Eduard Bloch. Because empathy is such a powerful emotion, even Hitler could sympathize with a Jew he knew and respected.

However, empathy is not enough. Our commitment to others goes beyond gut reactions; what is required is an unwavering, hardheaded sense of responsibility. Responsibility is based on profound sense of duty, and is not affected by emotional fluctuations. Even in the absence of tragedy, we must fulfill our responsibilities.

Responsibility is greatest towards those closest to you. Judah, when asking to take charge of his younger brother Benjamin, says to his father “I myself will guarantee his safety; you can hold me personally responsible for him. If I do not bring him back to you and set him here before you, I will bear the blame before you all my life.” Judah’s proclamation stands as the paradigm of Jewish responsibility, of how every Jew is responsible for one another.

Unfortunately, we have overlooked our responsibility towards one lonely, forgotten Jew. All of us should be asking ourselves this question: “Where is Gilad?” On June 25th, 2006, Gilad Shalit, a 22 year old Israeli, was abducted by Hamas; (it is certain that he was alive following his capture). Since then, he has not heard the voices of his parents, Noam and Aviva, and his brother and sister, Yoel and Hadas.

Sadly, other voices remain silent as well. Jews around the world, so capable of unity in the aftermath of tragedy, do very little to call for Gilad’s release. There is no dramatic video of Gilad to arouse our empathy; there is no sense of urgency for a crisis that has dragged on for over two years. It’s time we take our responsibility to Gilad seriously.

In Canada, The Canadian Rabbinic Caucus has initiated a letter writing campaign on Shalit’s behalf entitled “Where is Gilad?”. (One can go on the webpage http://www.cicweb.ca/ and quickly fill out a form that sends an e-mail to multiple members of the Canadian Parliament.).

We have to raise our voices with the Shalit family, and ask “Where is Gilad?’. But we also have to wonder why the Jewish community has done so little. Where are Judah’s descendents now, to say “you can hold me personally responsible for him”? Where is the state of Israel? Where is the Jewish community?

Where is our sense of responsibility?

It was a moment of Jewish inspiration. A thousand Montreal Jews huddled together in a synagogue to conduct a memorial service for the victims of the Mumbai massacre and the Mumbai Chabad House. Every type of Jew, including Satmar, Lubavitcher and Belzer Chassidim, Reform, Conservative, Orthodox, Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews, all came to the memorial. It was a powerful display of Jewish unity.

But after the inspiration, I was left with disappointment. The evening of course was touching and meaningful, but I was left with a nagging doubt: would this unity last? Yes, we Jews come together when things are difficult. Much like the old saying that “there are no atheists in foxholes”, there are no quarrels during tragedies; disasters have the unique ability to unite Jews together in a common cause. Bloodshed brings Jews together.

But when things get a little more comfortable, our unity fades. During the difficult days at the beginning of the Intifada, thousands of Jews, shocked by the images they saw on their TV screens, came out to rallies in support of the State of Israel. It was a critical juncture, a time “when the chips were down”, and even ultra-Orthodox Jews who wouldn’t consider themselves “Zionists” came to support the Jewish State. But once the violence quieted down, people were less willing to give their active support to Israel. Jewish unity is much more difficult to achieve in good times.

In difficult times, our hearts are touched by another person’s suffering. This powerful emotion, empathy, can affect even the most evil of human beings. While murdering six million other Jews, Adolf Hitler went out of his way to spare the life of his mother’s Jewish Doctor, Eduard Bloch. Because empathy is such a powerful emotion, even Hitler could sympathize with a Jew he knew and respected.

However, empathy is not enough. Our commitment to others goes beyond gut reactions; what is required is an unwavering, hardheaded sense of responsibility. Responsibility is based on profound sense of duty, and is not affected by emotional fluctuations. Even in the absence of tragedy, we must fulfill our responsibilities.

Responsibility is greatest towards those closest to you. Judah, when asking to take charge of his younger brother Benjamin, says to his father “I myself will guarantee his safety; you can hold me personally responsible for him. If I do not bring him back to you and set him here before you, I will bear the blame before you all my life.” Judah’s proclamation stands as the paradigm of Jewish responsibility, of how every Jew is responsible for one another.

Unfortunately, we have overlooked our responsibility towards one lonely, forgotten Jew. All of us should be asking ourselves this question: “Where is Gilad?” On June 25th, 2006, Gilad Shalit, a 22 year old Israeli, was abducted by Hamas; (it is certain that he was alive following his capture). Since then, he has not heard the voices of his parents, Noam and Aviva, and his brother and sister, Yoel and Hadas.

Sadly, other voices remain silent as well. Jews around the world, so capable of unity in the aftermath of tragedy, do very little to call for Gilad’s release. There is no dramatic video of Gilad to arouse our empathy; there is no sense of urgency for a crisis that has dragged on for over two years. It’s time we take our responsibility to Gilad seriously.

In Canada, The Canadian Rabbinic Caucus has initiated a letter writing campaign on Shalit’s behalf entitled “Where is Gilad?”. (One can go on the webpage http://www.cicweb.ca/ and quickly fill out a form that sends an e-mail to multiple members of the Canadian Parliament.).

We have to raise our voices with the Shalit family, and ask “Where is Gilad?’. But we also have to wonder why the Jewish community has done so little. Where are Judah’s descendents now, to say “you can hold me personally responsible for him”? Where is the state of Israel? Where is the Jewish community?

Where is our sense of responsibility?

Thursday, December 04, 2008

Parsha Inspiration - The Mumbai Massacre

Second installment of this new project - a point of inspiration on the parsha or current events, captured on video for youtube.

A huge thank you to Lorne Lieberman for chasing me for 2 years to do this, and Jacob Aspler for doing the video.Please send me your comments and thoughts on this.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HQ6CkMyBSfc

Wednesday, December 03, 2008

Shabbat For Gilad Shalit - Articles and Links

Canadian Jewish News, 12-3-08

Jewish Tribune, 12-2-08

CIC website (letter writing form on top right hand corner)

Canadian Rabbinic Caucus page at CIC

Facebook Page (login required)

Canadian Jewish News, 12-3-08

Jewish Tribune, 12-2-08

CIC website (letter writing form on top right hand corner)

Canadian Rabbinic Caucus page at CIC

Facebook Page (login required)

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

Parsha Inspiration

This is a new project - a point of inspiration on the parsha, captured on video for youtube.

A huge thank you to Lorne Lieberman for chasing me for 2 years to do this, and Jacob Aspler for doing the video.

Please send me your comments and thoughts on this.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ohu6G09UBqw

This is a new project - a point of inspiration on the parsha, captured on video for youtube.

A huge thank you to Lorne Lieberman for chasing me for 2 years to do this, and Jacob Aspler for doing the video.

Please send me your comments and thoughts on this.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ohu6G09UBqw

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

Why Is 25 the New 15?

When it comes to age, it seems that subtract by ten is the new rule of thumb. Everyone is living longer, and at all stages in life, people seem to be ten years younger than their actual age. Our current crop of baby boomers, healthier and more youthful than previous generations, has sworn never to grow old. Indeed, fifty is the new forty.

Subtracting by ten works well with older ages; but what about our twenty-somethings? It seems that younger people are maturing at a slower pace as well. As David Brooks noted in the New York Times: “People….. tend to define adulthood by certain accomplishments — moving away from home, becoming financially independent, getting married and starting a family. In 1960, roughly 70 percent of 30-year-olds had achieved these things. By 2000, fewer than 40 percent of 30-year-olds had done the same.”

Twentysomethings are maturing far slower than their parents. People in their middle twenties now seem to be experiencing a second adolescence. Why is 25 the new 15?

The relative immaturity of our contemporary twentysomethings is rooted in the positive phenomena of peace and prosperity. Young people in North America need not serve in the military, and most don’t. Middle class twentysomethings can expect to have their parents provide them with cars, clothing, and cellphones. This dependence on one’s parents continues well after high school. Children who are taking entry level jobs are unwilling to live entry level lifestyles, and their parents are willing to indulge them by paying the rent and covering their credit cards. As one twentysomething observer noted:

The fact is, my peers who flood out of designer stores, arms adorned with shopping bags, wouldn't be able to afford their purchases without ringing up a massive credit-card debt. By continuing to provide for their twentysomething kids, parents hinder their children's ability to be financially responsible.

Or, to put it in simple English: we’re spoiling our kids. That’s why 25 is the new 15.

The problem of spoiling children is an old one. Jacob who works hard all his life to achieve success, spoils his beloved son Joseph, giving him fancy clothes and special treatment. It’s no wonder that the Midrash says that that Joseph was immature! The problem of spoiled children is an old phenomenon; we are simply lucky enough today to have the resources to spoil our children.

Unfortunately, handing our children the good life on a silver platter can do more harm than good. A powerful Kabbalistic idea popularized by the Ramchal is “the bread of shame”. If someone is handed a loaf of bread without earning it, they lose their dignity; and even if the recipient may be happy to live life on easy street, the fact that his achievements are unearned is an embarrassment to a man created in the image of God. To truly be a “man”, one must be dignified and independent, someone who is able to earn his own way. Trust funds may pay your credit card bills, but they can also destroy your character.

This issue is of great importance to the Jewish community. In one generation, the much of the Jewish world has gone from deprivation and suffering to breathtaking wealth. It is normal for a community of immigrants and survivors to want to hand everything to the next generation on a silver platter. And so we give too much to our kids. Hard work becomes unimportant when we hand undeserving young men the keys to successful businesses. Spiritual values get lost when materialism becomes the operating principle. And so we make Bar and Bat Mitzvahs that are so over the top they lend themselves to parody, and are sometimes so garish (and expensive) they end up on the gossip pages of tabloids. Our community has survived, and even thrived in the most difficult of times due to faith, community and character. Ironically, our community’s material success threatens to destroy the very values it was built on.

Adolescent 25 year olds are not an automatic outcome of success; it happens when we forget transmit our values to the next generation. If our priority is to provide our children with values, not valuables, we will have children to be proud of.

When it comes to age, it seems that subtract by ten is the new rule of thumb. Everyone is living longer, and at all stages in life, people seem to be ten years younger than their actual age. Our current crop of baby boomers, healthier and more youthful than previous generations, has sworn never to grow old. Indeed, fifty is the new forty.

Subtracting by ten works well with older ages; but what about our twenty-somethings? It seems that younger people are maturing at a slower pace as well. As David Brooks noted in the New York Times: “People….. tend to define adulthood by certain accomplishments — moving away from home, becoming financially independent, getting married and starting a family. In 1960, roughly 70 percent of 30-year-olds had achieved these things. By 2000, fewer than 40 percent of 30-year-olds had done the same.”

Twentysomethings are maturing far slower than their parents. People in their middle twenties now seem to be experiencing a second adolescence. Why is 25 the new 15?

The relative immaturity of our contemporary twentysomethings is rooted in the positive phenomena of peace and prosperity. Young people in North America need not serve in the military, and most don’t. Middle class twentysomethings can expect to have their parents provide them with cars, clothing, and cellphones. This dependence on one’s parents continues well after high school. Children who are taking entry level jobs are unwilling to live entry level lifestyles, and their parents are willing to indulge them by paying the rent and covering their credit cards. As one twentysomething observer noted:

The fact is, my peers who flood out of designer stores, arms adorned with shopping bags, wouldn't be able to afford their purchases without ringing up a massive credit-card debt. By continuing to provide for their twentysomething kids, parents hinder their children's ability to be financially responsible.

Or, to put it in simple English: we’re spoiling our kids. That’s why 25 is the new 15.

The problem of spoiling children is an old one. Jacob who works hard all his life to achieve success, spoils his beloved son Joseph, giving him fancy clothes and special treatment. It’s no wonder that the Midrash says that that Joseph was immature! The problem of spoiled children is an old phenomenon; we are simply lucky enough today to have the resources to spoil our children.

Unfortunately, handing our children the good life on a silver platter can do more harm than good. A powerful Kabbalistic idea popularized by the Ramchal is “the bread of shame”. If someone is handed a loaf of bread without earning it, they lose their dignity; and even if the recipient may be happy to live life on easy street, the fact that his achievements are unearned is an embarrassment to a man created in the image of God. To truly be a “man”, one must be dignified and independent, someone who is able to earn his own way. Trust funds may pay your credit card bills, but they can also destroy your character.

This issue is of great importance to the Jewish community. In one generation, the much of the Jewish world has gone from deprivation and suffering to breathtaking wealth. It is normal for a community of immigrants and survivors to want to hand everything to the next generation on a silver platter. And so we give too much to our kids. Hard work becomes unimportant when we hand undeserving young men the keys to successful businesses. Spiritual values get lost when materialism becomes the operating principle. And so we make Bar and Bat Mitzvahs that are so over the top they lend themselves to parody, and are sometimes so garish (and expensive) they end up on the gossip pages of tabloids. Our community has survived, and even thrived in the most difficult of times due to faith, community and character. Ironically, our community’s material success threatens to destroy the very values it was built on.

Adolescent 25 year olds are not an automatic outcome of success; it happens when we forget transmit our values to the next generation. If our priority is to provide our children with values, not valuables, we will have children to be proud of.

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

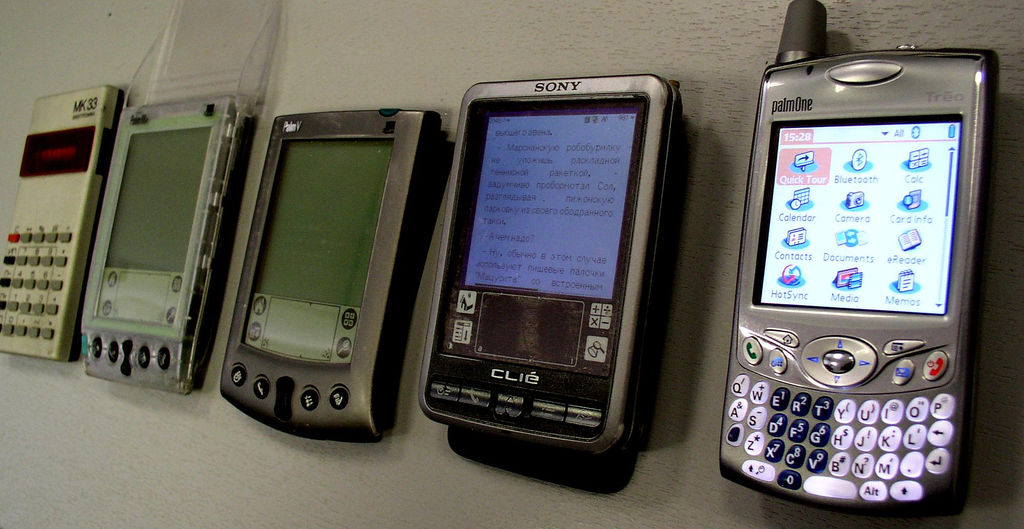

Buzz, Buzz, I’ve Got Blackberry Brain

How long will you focus on this article? Will your cellphone ring? Will you check your e-mail or your Blackberry?

Attention spans have been dramatically (….oops, wait, I have an e-mail…) shortened. A horde of digital devices emitting beeps, bells and buzzes demand our deliberation. Who has the time to think when we have text messages and e-mails that demand immediate responses? Our electronic servants are exacting taskmasters.

Even though I’m a Rabbi, I’m an authority on digital disruption; I’m a Blackberry toting, internet blogging, cellphone conferencing kind of guy. And for a while, I kept my Blackberry on “buzz” (which, for those of you who are unfamiliar with Blackberries, means that my Blackberry would vibrate every time an e-mail arrived). Eventually, I started to feel phantom buzzing on my hip, even when I took the Blackberry off; my brain continued buzzing, even when my Blackberry was off. This little electronic gadget was starting to drive me crazy, one buzz at a time.

What I was suffering from was “Blackberry Brain”. With this condition, virtual reality displaces actual reality, and urgent messages trump meaningful moments. Over-reliance on electronic forms of communication alter your relationship to reality.

It’s not surprising that researchers in several countries have documented addictive behaviors in relation to cellphones and personal digital assistants (PDA’s). These devices, with their ever insistent beeping, (with a customized ringtone, of course), demand your constant attention; eventually, you feel empty unless you are typing, tapping or texting something to somebody.

Our electronic masters take advantage of a design flaw us humans have. Human beings have a propensity to fixate on details.

Even in the area of religion, overzealousness in the pursuit of piety can be profoundly destructive. The Talmud refers to the “foolish pious man” who refuses to save a drowning woman because it would be a breach of modesty. This fool is so obsessed with sexual impropriety he’d rather allow a drowning woman to die. Details, in this case get in the way; the pious fool is blinded by his petty pieties, and can no longer see the bigger picture.

We may not be pious fools, but a lot of us are PDA fools, victims of Blackberry brain. We love the wide ranging communications abilities that our Blackberries give us, as in “look, I just e-mailed my friend in Hong Kong”; but if we fixate on this buzzing busybody of a Blackberry, we will forget the people standing in front of us. I must admit, that there are times that arrive home (late) to a wife and children who want to say hello, but instead I’m typing away on the Blackberry, knocking off the last couple of e-mails of the day. (I’d have to assume I’m not the only person who does this). At that moment, when “just one more e-mail” gets in the way, we are experiencing the first symptoms of Blackberry Brain.

Blackberry Brain can be very destructive if you don’t nip it in the bud. As the condition worsens, we completely forget how to focus on other people. Old friends go out for lunch, and instead of catching up, they listen to each other with a half an ear while tapping out quick e-mails; as Blackberry Brain worsens, our old friendships are slowly replaced with shiny new gadgets, soulless devices that just make a lot of noise.

To my mind, the affliction of Blackberry Brain underlines the ever increasing importance of the Sabbath. More than ever, we need a night when we turn off the Blackberry and close our cellphones; more than ever, we need a night when the TV and computer remain dark. We need to find a sacred block of time to gather our family for dinner and conversation. Our technology drenched age needs quiet tranquil moments where authentic, person to person connections can flourish. The Sabbath is the perfect time for that to happen. Because connections come from your soul, not from your cellphone.

How long will you focus on this article? Will your cellphone ring? Will you check your e-mail or your Blackberry?

Attention spans have been dramatically (….oops, wait, I have an e-mail…) shortened. A horde of digital devices emitting beeps, bells and buzzes demand our deliberation. Who has the time to think when we have text messages and e-mails that demand immediate responses? Our electronic servants are exacting taskmasters.

Even though I’m a Rabbi, I’m an authority on digital disruption; I’m a Blackberry toting, internet blogging, cellphone conferencing kind of guy. And for a while, I kept my Blackberry on “buzz” (which, for those of you who are unfamiliar with Blackberries, means that my Blackberry would vibrate every time an e-mail arrived). Eventually, I started to feel phantom buzzing on my hip, even when I took the Blackberry off; my brain continued buzzing, even when my Blackberry was off. This little electronic gadget was starting to drive me crazy, one buzz at a time.

What I was suffering from was “Blackberry Brain”. With this condition, virtual reality displaces actual reality, and urgent messages trump meaningful moments. Over-reliance on electronic forms of communication alter your relationship to reality.

It’s not surprising that researchers in several countries have documented addictive behaviors in relation to cellphones and personal digital assistants (PDA’s). These devices, with their ever insistent beeping, (with a customized ringtone, of course), demand your constant attention; eventually, you feel empty unless you are typing, tapping or texting something to somebody.

Our electronic masters take advantage of a design flaw us humans have. Human beings have a propensity to fixate on details.

Even in the area of religion, overzealousness in the pursuit of piety can be profoundly destructive. The Talmud refers to the “foolish pious man” who refuses to save a drowning woman because it would be a breach of modesty. This fool is so obsessed with sexual impropriety he’d rather allow a drowning woman to die. Details, in this case get in the way; the pious fool is blinded by his petty pieties, and can no longer see the bigger picture.

We may not be pious fools, but a lot of us are PDA fools, victims of Blackberry brain. We love the wide ranging communications abilities that our Blackberries give us, as in “look, I just e-mailed my friend in Hong Kong”; but if we fixate on this buzzing busybody of a Blackberry, we will forget the people standing in front of us. I must admit, that there are times that arrive home (late) to a wife and children who want to say hello, but instead I’m typing away on the Blackberry, knocking off the last couple of e-mails of the day. (I’d have to assume I’m not the only person who does this). At that moment, when “just one more e-mail” gets in the way, we are experiencing the first symptoms of Blackberry Brain.

Blackberry Brain can be very destructive if you don’t nip it in the bud. As the condition worsens, we completely forget how to focus on other people. Old friends go out for lunch, and instead of catching up, they listen to each other with a half an ear while tapping out quick e-mails; as Blackberry Brain worsens, our old friendships are slowly replaced with shiny new gadgets, soulless devices that just make a lot of noise.

To my mind, the affliction of Blackberry Brain underlines the ever increasing importance of the Sabbath. More than ever, we need a night when we turn off the Blackberry and close our cellphones; more than ever, we need a night when the TV and computer remain dark. We need to find a sacred block of time to gather our family for dinner and conversation. Our technology drenched age needs quiet tranquil moments where authentic, person to person connections can flourish. The Sabbath is the perfect time for that to happen. Because connections come from your soul, not from your cellphone.

Thursday, September 18, 2008

When Saviors Fail

Health care workers life lives of deep frustration.

Doctors and nurses enter the medical profession in the hope of saving lives. Unfortunately, they must watch their patients die on a daily basis. Failure leaves a bitter taste in any person’s mouth; but for those sworn to save and redeem, failure is particularly galling, and questions their very identity.

Indeed, Moses, after the failure of his first mission to Pharaoh, protests to God:

“Why have you brought all this trouble on your own people, Lord? Why did you send me? Ever since I came to Pharaoh as your spokesman, he has been even more brutal to your people. And you have done nothing to rescue them!”

Moses doubts his own usefulness as a messenger. It’s not easy for a savior to fail.

I was thinking of this verse after reading an excellent account by Theresa Brown about what it’s like for a new nurse to watch a patient die:

At my job, people die.

That’s hardly our intention, but they die nonetheless.

Usually it’s at the end of a long struggle — we have done everything modern medicine can do and then some, but we can’t save them. ……. And then there are the other deaths: quick and rare, where life leaves a body in minutes. In my hospital these deaths are “Condition A’s.” The “A” stands for arrest, as in cardiac arrest, as in this patient’s heart has all of a sudden stopped beating and we need to try to restart it.

I am a new nurse, and recently I had my first Condition A. My patient, a particularly nice older woman with lung cancer, had been, as we say, “fine,” with no complaints but a low-grade fever she’d had off and on for a couple of days. She had come in because she was coughing up blood, a problem we had resolved, and she was set for discharge that afternoon.

After a routine assessment in the morning, I left her in the care of a nursing student and moved on to other patients, thinking I was going to have a relatively calm day. About half an hour later an aide called me: “Theresa, they need you in 1022.”

I stopped what I was doing and walked over to her room. The nurse leaving the room said, “She’s spitting up blood,” and went to the nurses’ station to call her doctor.

The patient tried to stand up so the blood would flow into a nearby trash can, and I told her, “No, don’t stand up.” She sat back down, started shaking and then collapsed backward on the bed.

“Is it condition time?” asked the other nurse.

“Call the code!” I yelled. “Call the code!”

The next few moments I can only describe as surreal. I felt for a pulse and there wasn’t one. I started doing CPR. On the overhead loudspeaker, a voice called out, “Condition A.” ….

They worked on her for half an hour…… And (then) my patient was dead. She had been dead when she fell back on the bed and she stayed dead through all the effort to save her, while blood and tissue bubbled out of her and the suction clogged with particles spilling from her lungs. Everyone did what she knew how to do to save her. She could not be saved.

Doctors and nurses cannot save everyone; even Moses had his failures. Yes, saviors fail - but failures can be saviors too. We just have to remember, every time we fail, to keep on going, because “it’s not incumbent upon us to complete the job, but we can’t quit either.”

Health care workers life lives of deep frustration.

Doctors and nurses enter the medical profession in the hope of saving lives. Unfortunately, they must watch their patients die on a daily basis. Failure leaves a bitter taste in any person’s mouth; but for those sworn to save and redeem, failure is particularly galling, and questions their very identity.

Indeed, Moses, after the failure of his first mission to Pharaoh, protests to God:

“Why have you brought all this trouble on your own people, Lord? Why did you send me? Ever since I came to Pharaoh as your spokesman, he has been even more brutal to your people. And you have done nothing to rescue them!”

Moses doubts his own usefulness as a messenger. It’s not easy for a savior to fail.

I was thinking of this verse after reading an excellent account by Theresa Brown about what it’s like for a new nurse to watch a patient die:

At my job, people die.

That’s hardly our intention, but they die nonetheless.

Usually it’s at the end of a long struggle — we have done everything modern medicine can do and then some, but we can’t save them. ……. And then there are the other deaths: quick and rare, where life leaves a body in minutes. In my hospital these deaths are “Condition A’s.” The “A” stands for arrest, as in cardiac arrest, as in this patient’s heart has all of a sudden stopped beating and we need to try to restart it.

I am a new nurse, and recently I had my first Condition A. My patient, a particularly nice older woman with lung cancer, had been, as we say, “fine,” with no complaints but a low-grade fever she’d had off and on for a couple of days. She had come in because she was coughing up blood, a problem we had resolved, and she was set for discharge that afternoon.

After a routine assessment in the morning, I left her in the care of a nursing student and moved on to other patients, thinking I was going to have a relatively calm day. About half an hour later an aide called me: “Theresa, they need you in 1022.”

I stopped what I was doing and walked over to her room. The nurse leaving the room said, “She’s spitting up blood,” and went to the nurses’ station to call her doctor.

The patient tried to stand up so the blood would flow into a nearby trash can, and I told her, “No, don’t stand up.” She sat back down, started shaking and then collapsed backward on the bed.

“Is it condition time?” asked the other nurse.

“Call the code!” I yelled. “Call the code!”

The next few moments I can only describe as surreal. I felt for a pulse and there wasn’t one. I started doing CPR. On the overhead loudspeaker, a voice called out, “Condition A.” ….

They worked on her for half an hour…… And (then) my patient was dead. She had been dead when she fell back on the bed and she stayed dead through all the effort to save her, while blood and tissue bubbled out of her and the suction clogged with particles spilling from her lungs. Everyone did what she knew how to do to save her. She could not be saved.

Doctors and nurses cannot save everyone; even Moses had his failures. Yes, saviors fail - but failures can be saviors too. We just have to remember, every time we fail, to keep on going, because “it’s not incumbent upon us to complete the job, but we can’t quit either.”

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

A Father’s Aspirations

These are the notes to the speech I gave at my twin son's Bar Mitzvah. (I've edited it to make it a bit more readable, but it's still in note form.)

What Does a Father Hope for?

Boys, when a father looks at his children, what do you think he hopes for? What do you think he prays for? What are his aspirations?

Now you might think there’s an easy answer:

He wants his children to be happy

To be content

To have good fortune.

And it’s true, that for the father in me that’s all I would want.

But I am a Jewish father…

If that’s all Jewish fathers ever wanted, there wouldn’t be a Jewish people.

If all we ever wanted from our children is to be happy and content, the Jewish people would have disappeared years ago.

Because it would have been a lot easier to give up; it would have been a lot happier to forget about being Jewish, and just live happy lives.

But we are here because Jewish fathers and mothers wanted more than happiness from their children.

The hopes and aspirations of these fathers and mothers was for their children to carry on the traditions of Avraham and Sarah, of Moshe Rabbeinu and Beit Hillel and Rabbi Akiva.

And I want to talk to you about these aspirations: the aspirations of a Jewish Father.

Actually, I had way too many aspirations to talk about so I had to leave some out – I’ll talk to you guys about them for next couple of decades, God willing!

Aspiration I: To Become a Fireman

You haven’t wanted to be a fireman in a couple of years, right? Well, actually I’d like you to reconsider. (And on the Friday night before the Bar Mitzvah, at the family dinner, a napkin caught fire and the fire alarm went off, and 15 firemen showed up!! - coincidence?)

The Midrash describes Abraham’s search for God to a man who sees a burning castle, and declares “is it possible this castle doesn’t have an owner (who cares about it’s welfare)?”.

Abraham sees the world around him as similar to a burning castle. He immediately understands two things:

There must be an architect who built it, and owns it, and that we must put out the fire.

At this moment, Avraham arrives at the Jewish mission: to be a fireman.

A Jewish fireman must do two things: he must search for, and know God, and at the same time, he must transform God’s world. A Jew must put out the fires of imperfection that rage around us.

And that’s what I want from you Akiva and Hillel; to be Jewish firemen.

Look around this room:

There are Rabbis: people who have dedicated their lives to God’s Torah and to Avraham’s mission.

They are firemen. And my greatest wish for you is that you will become Talmidei Chachamim, Torah scholars.

There are doctors and engineers and teachers and social workers: people who make the world a better place, one person at a time.

They are firemen.

There are volunteers; people who give their time and money and hearts.

Why do they do it? because they love other people. And follow the ideal of v’ahavta l’reacha kamocha, love your neighbor as yourself. Which by the way, was the central teaching of your namesakes, the Rabbis Hillel and Akiva, rabbis who lived 2,000 years ago.

These volunteers, people who love other people, are firemen.

There are activists, who refuse to accept the evil and corruption in the world:

People who come to rallies and organize to denounce the genocide in Darfur, and suicide bombings in Jerusalem, the Chinese in Tibet, and Kassam rockets in Sderot.

They are firemen!!

And boys, I really want you to be firemen too.

Aspiration II: To Love Your Family

Family is perhaps greatest lesson taught in the Book of Genesis. The entire point of Sefer Bereishit is to love your family, although it takes much struggle, indeed the entire book, to get to the point of family togetherness.

I am privileged to be part of a family with such devotion.

And that’s why today we have family members from Toronto, New York, New Jersey, Baltimore, North Carolina, Brazil and Israel.

And you know Mommy’s family; Bubbie and Zaide, and Rona and Brad and Sari.

Any you know they will do absolutely anything for us, and they are always there for us all of the time.

And, on a personal level. I cannot express in words the devotion Bubby has given to me and all her children all of her life, nor can I express enough thanks to my older brother Mayer and sisters Sarah and Chavi, as well Yossi and Adina, who did so much to raise me.

And of course, Mommy.

You know Rabbi Akiva said to his students about his wife Rachel, the most wonderful thing ever said about a spouse:

Sheli v’shelachem shelah hee – what you and I have accomplished, belongs to her.

And this is Mommy, who is absolutely devoted to me and to the shul, and to you, and to your school, and to her friends, and to her community.

She has twice arrived in communities where she knew no one, in order to serve the Jewish people. And she is always at home, ready to serve her family with a smile.

I pray the two of you will find spouses as wonderful as her.

Aspiration III: Pass the Test

The final, and most important hope that I have for you, is that you pass the test.

This is not an aspiration we want to have, but one we are forced to have.

Every Jewish father knows that in life, there have been many tests. The tests start with Abraham's life,where he was tested 10 times. But these seem to continue over and over again in history.

Actually, life always brings many tests.

You will be forced to show your determination and courage.

You will have to work hard without quitting.

You know your namesakes, Rabbis Akiva and Hillel, were determined.

Akiva was an ignorant man. At age 40 he learned the aleph bet!!

Akiva did not give up and say he was too old.

Akiva did not give up and say it is too hard.

Akiva succeeded because he was determined.

Hillel was a poor man. He couldn’t even pay the entrance fee for the Yeshiva. He climbed on a roof just to poke his head into the skylight and hear words of Torah.

Hillel did not give up because he was broke.

Hillel did not get discouraged because life was hard.

Hillel succeeded because he wasn’t a quitter.

And that is the greatest hope of a Jewish father: that he has children who can assume this responsibility, to carry on a tradition, even though it can be tough at times.

To be determined.

To have courage.

And by the way, courage doesn’t mean that you aren’t being afraid. What courage means is that you continue to go on despite the fear.

Why Today's Miracle is So Sweet

Today, it is hard for me not to think about the challenges in my own family as we arrive here.

As you know, my grandfather perished in the Holocaust.

Bubby, my mother is a survivor of the Holocaust.

And my father Chaim, died in a car accident before I was born, and I am named after him.

It was a long road getting here.

And all of those tests do two things:

They make my aspirations as a Jewish father stronger. I want you to be firemen!!

But at the same time, it makes the miracle of today’s celebration sweeter.

13 years ago, a miracle occurred in the Jack D. Weiler Hospital in the Bronx.

Akiva Meir and Hillel Aryeh Steinmetz were born.

And your birth was not just a miracle for me, but for everybody in this room.

Because 3,800 years after Abraham and Sarah left on their mission

3,300 years after the Exodus and the giving of the Torah

and 60 years after the Shoah

There are still another generation of Jews being born. Two more Jewish firemen have arrived on the scene.

May God bless you, and may you give yiddishe nakhes to everyone in this room.

Mazel tov!

These are the notes to the speech I gave at my twin son's Bar Mitzvah. (I've edited it to make it a bit more readable, but it's still in note form.)

What Does a Father Hope for?

Boys, when a father looks at his children, what do you think he hopes for? What do you think he prays for? What are his aspirations?

Now you might think there’s an easy answer:

He wants his children to be happy

To be content

To have good fortune.

And it’s true, that for the father in me that’s all I would want.

But I am a Jewish father…

If that’s all Jewish fathers ever wanted, there wouldn’t be a Jewish people.

If all we ever wanted from our children is to be happy and content, the Jewish people would have disappeared years ago.

Because it would have been a lot easier to give up; it would have been a lot happier to forget about being Jewish, and just live happy lives.

But we are here because Jewish fathers and mothers wanted more than happiness from their children.

The hopes and aspirations of these fathers and mothers was for their children to carry on the traditions of Avraham and Sarah, of Moshe Rabbeinu and Beit Hillel and Rabbi Akiva.

And I want to talk to you about these aspirations: the aspirations of a Jewish Father.

Actually, I had way too many aspirations to talk about so I had to leave some out – I’ll talk to you guys about them for next couple of decades, God willing!

Aspiration I: To Become a Fireman

You haven’t wanted to be a fireman in a couple of years, right? Well, actually I’d like you to reconsider. (And on the Friday night before the Bar Mitzvah, at the family dinner, a napkin caught fire and the fire alarm went off, and 15 firemen showed up!! - coincidence?)

The Midrash describes Abraham’s search for God to a man who sees a burning castle, and declares “is it possible this castle doesn’t have an owner (who cares about it’s welfare)?”.

Abraham sees the world around him as similar to a burning castle. He immediately understands two things:

There must be an architect who built it, and owns it, and that we must put out the fire.

At this moment, Avraham arrives at the Jewish mission: to be a fireman.

A Jewish fireman must do two things: he must search for, and know God, and at the same time, he must transform God’s world. A Jew must put out the fires of imperfection that rage around us.

And that’s what I want from you Akiva and Hillel; to be Jewish firemen.

Look around this room:

There are Rabbis: people who have dedicated their lives to God’s Torah and to Avraham’s mission.

They are firemen. And my greatest wish for you is that you will become Talmidei Chachamim, Torah scholars.

There are doctors and engineers and teachers and social workers: people who make the world a better place, one person at a time.

They are firemen.

There are volunteers; people who give their time and money and hearts.

Why do they do it? because they love other people. And follow the ideal of v’ahavta l’reacha kamocha, love your neighbor as yourself. Which by the way, was the central teaching of your namesakes, the Rabbis Hillel and Akiva, rabbis who lived 2,000 years ago.

These volunteers, people who love other people, are firemen.

There are activists, who refuse to accept the evil and corruption in the world:

People who come to rallies and organize to denounce the genocide in Darfur, and suicide bombings in Jerusalem, the Chinese in Tibet, and Kassam rockets in Sderot.

They are firemen!!

And boys, I really want you to be firemen too.

Aspiration II: To Love Your Family

Family is perhaps greatest lesson taught in the Book of Genesis. The entire point of Sefer Bereishit is to love your family, although it takes much struggle, indeed the entire book, to get to the point of family togetherness.

I am privileged to be part of a family with such devotion.

And that’s why today we have family members from Toronto, New York, New Jersey, Baltimore, North Carolina, Brazil and Israel.

And you know Mommy’s family; Bubbie and Zaide, and Rona and Brad and Sari.

Any you know they will do absolutely anything for us, and they are always there for us all of the time.

And, on a personal level. I cannot express in words the devotion Bubby has given to me and all her children all of her life, nor can I express enough thanks to my older brother Mayer and sisters Sarah and Chavi, as well Yossi and Adina, who did so much to raise me.

And of course, Mommy.

You know Rabbi Akiva said to his students about his wife Rachel, the most wonderful thing ever said about a spouse:

Sheli v’shelachem shelah hee – what you and I have accomplished, belongs to her.

And this is Mommy, who is absolutely devoted to me and to the shul, and to you, and to your school, and to her friends, and to her community.

She has twice arrived in communities where she knew no one, in order to serve the Jewish people. And she is always at home, ready to serve her family with a smile.

I pray the two of you will find spouses as wonderful as her.

Aspiration III: Pass the Test

The final, and most important hope that I have for you, is that you pass the test.

This is not an aspiration we want to have, but one we are forced to have.

Every Jewish father knows that in life, there have been many tests. The tests start with Abraham's life,where he was tested 10 times. But these seem to continue over and over again in history.

Actually, life always brings many tests.

You will be forced to show your determination and courage.

You will have to work hard without quitting.

You know your namesakes, Rabbis Akiva and Hillel, were determined.

Akiva was an ignorant man. At age 40 he learned the aleph bet!!

Akiva did not give up and say he was too old.

Akiva did not give up and say it is too hard.

Akiva succeeded because he was determined.

Hillel was a poor man. He couldn’t even pay the entrance fee for the Yeshiva. He climbed on a roof just to poke his head into the skylight and hear words of Torah.

Hillel did not give up because he was broke.

Hillel did not get discouraged because life was hard.

Hillel succeeded because he wasn’t a quitter.

And that is the greatest hope of a Jewish father: that he has children who can assume this responsibility, to carry on a tradition, even though it can be tough at times.

To be determined.

To have courage.

And by the way, courage doesn’t mean that you aren’t being afraid. What courage means is that you continue to go on despite the fear.

Why Today's Miracle is So Sweet

Today, it is hard for me not to think about the challenges in my own family as we arrive here.

As you know, my grandfather perished in the Holocaust.

Bubby, my mother is a survivor of the Holocaust.

And my father Chaim, died in a car accident before I was born, and I am named after him.

It was a long road getting here.

And all of those tests do two things:

They make my aspirations as a Jewish father stronger. I want you to be firemen!!

But at the same time, it makes the miracle of today’s celebration sweeter.

13 years ago, a miracle occurred in the Jack D. Weiler Hospital in the Bronx.

Akiva Meir and Hillel Aryeh Steinmetz were born.

And your birth was not just a miracle for me, but for everybody in this room.

Because 3,800 years after Abraham and Sarah left on their mission

3,300 years after the Exodus and the giving of the Torah

and 60 years after the Shoah

There are still another generation of Jews being born. Two more Jewish firemen have arrived on the scene.

May God bless you, and may you give yiddishe nakhes to everyone in this room.

Mazel tov!

Article About Blog + Apology

Hi! It's been a little while, yes. I've been busy, mostly with the wonderful Bar Mitzvah of my twin sons, Akiva and Hillel. (Who would have thought that a 900 person Bar Mitzvah could be so much work?!).

Anyway, I'll be back to blogging real soon, even with Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur around the corner. (I will post some of my speech from the Bar Mitzvah in the near future.)

So, considering that I've neglected to update the blog in a month, you could imagine my embarrassment when Dave Gordon's wonderful article about this blog appeared in this week's CJN. It's like being featured in a jumbotron closeup at a sporting event, while you have a ketchup stain on your shirt.

But I will be back at blogging soon!!!

Hi! It's been a little while, yes. I've been busy, mostly with the wonderful Bar Mitzvah of my twin sons, Akiva and Hillel. (Who would have thought that a 900 person Bar Mitzvah could be so much work?!).

Anyway, I'll be back to blogging real soon, even with Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur around the corner. (I will post some of my speech from the Bar Mitzvah in the near future.)

So, considering that I've neglected to update the blog in a month, you could imagine my embarrassment when Dave Gordon's wonderful article about this blog appeared in this week's CJN. It's like being featured in a jumbotron closeup at a sporting event, while you have a ketchup stain on your shirt.

But I will be back at blogging soon!!!

Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Junk Food For the Soul

Nike. Hermes. Pepsi. Versace. Starbucks. Mercedes. Armani.

You know these names, and so do millions of people worldwide. They are examples of “brands”, trademarks used by manufacturers and designers to distinguish their goods. Today, brand names are a multi-billion dollar economic juggernaut that drives the global economy.

Brands may be great for business, but they’re bad for the soul. Brands used to be about quality and style, and a good brand meant a reliable high quality product. (And a brand that lost its reputation was mocked – I remember when a certain car company was ridiculed by the phrase Fix Or Repair Daily). But contemporary brands are more about image than about quality; the logo on the front of a polo shirt is a substitute for personal identity.

It’s usually wise to avoid judging a book by its cover (or as the Mishnah puts it, judge a wine by the bottle). But with brands, we are encouraged to believe that changing our cover will change our personality. Ad taglines imply that the brand’s image will become our own. If we drink Pepsi, we will “think young”, and if we buy an Apple computer we will “think different”. Nike sneakers announce that you are a proactive person who will “just do it”, and true love requires a diamond, because “a diamond is forever”. As Susan Fournier, a professor at Harvard Business School put it: "People look at brands as carriers of symbolic language and forget that a brand's first purpose is to close the sale."

Brands are junk food for the soul. The search for identity is a powerful spiritual force that encourages people to live meaningful lives. Even when man has all of his other needs met, he still needs to create a spiritual identity. As the prophet Amos says: “Behold, the days come, says the Lord, that I will send a famine in the land. Not a famine of bread, nor a thirst for water, but a hunger to hear the words of God.”. A store bought brand identity substitutes ersatz meaning in place of spiritual depth.

The glamour and glitz of brands make them far more attractive than old fashioned spirituality. People contort themselves in order to own the Porsche or buy the Rolex. Among young upper middle class couples, there is what I call a “baby vs. BMW dilemma”. Should they have another child and live more modestly, or should they curtail their family in order to lease “the ultimate driving machine”?. In a materialistic, brand intoxicated culture, too many people choose BMW’s instead of babies. (Maybe babies just need to improve their brand image!)

Like junk food, brands are a tasty little pleasure when enjoyed in moderation. But like junk food, brands can replace a healthy spiritual identity with fashionable but hollow designer vanity.

And too many people have sold their souls for a logo.

Nike. Hermes. Pepsi. Versace. Starbucks. Mercedes. Armani.

You know these names, and so do millions of people worldwide. They are examples of “brands”, trademarks used by manufacturers and designers to distinguish their goods. Today, brand names are a multi-billion dollar economic juggernaut that drives the global economy.

Brands may be great for business, but they’re bad for the soul. Brands used to be about quality and style, and a good brand meant a reliable high quality product. (And a brand that lost its reputation was mocked – I remember when a certain car company was ridiculed by the phrase Fix Or Repair Daily). But contemporary brands are more about image than about quality; the logo on the front of a polo shirt is a substitute for personal identity.

It’s usually wise to avoid judging a book by its cover (or as the Mishnah puts it, judge a wine by the bottle). But with brands, we are encouraged to believe that changing our cover will change our personality. Ad taglines imply that the brand’s image will become our own. If we drink Pepsi, we will “think young”, and if we buy an Apple computer we will “think different”. Nike sneakers announce that you are a proactive person who will “just do it”, and true love requires a diamond, because “a diamond is forever”. As Susan Fournier, a professor at Harvard Business School put it: "People look at brands as carriers of symbolic language and forget that a brand's first purpose is to close the sale."

Brands are junk food for the soul. The search for identity is a powerful spiritual force that encourages people to live meaningful lives. Even when man has all of his other needs met, he still needs to create a spiritual identity. As the prophet Amos says: “Behold, the days come, says the Lord, that I will send a famine in the land. Not a famine of bread, nor a thirst for water, but a hunger to hear the words of God.”. A store bought brand identity substitutes ersatz meaning in place of spiritual depth.

The glamour and glitz of brands make them far more attractive than old fashioned spirituality. People contort themselves in order to own the Porsche or buy the Rolex. Among young upper middle class couples, there is what I call a “baby vs. BMW dilemma”. Should they have another child and live more modestly, or should they curtail their family in order to lease “the ultimate driving machine”?. In a materialistic, brand intoxicated culture, too many people choose BMW’s instead of babies. (Maybe babies just need to improve their brand image!)

Like junk food, brands are a tasty little pleasure when enjoyed in moderation. But like junk food, brands can replace a healthy spiritual identity with fashionable but hollow designer vanity.

And too many people have sold their souls for a logo.

Thursday, July 10, 2008

What Do You Have When You Have Nothing?

Natural disasters have dominated the news. In June there were the disastrous floods in the Midwest, and in July, wildfires ravaged Northern California. Thousands have watched their homes and possessions destroyed.

It is particularly painful to consider the fate of those who lived outside of flood or fire “range”, and were not insured. In a matter of hours, they watched the bulk of their assets disappear, along with their homes and communities. In natural disasters like these, lives are ravaged along with the countryside.

The question that nature forces upon the survivors of these catastrophes is simple: what do you have when you have nothing? It's a question that seems absurd at first; if you have lost everything, then you truly have nothing.

Actually, those of us who live comfortably are afraid of contemplating this question. We are driven more by a fear of loss than by any possibility of gain. (This has been demonstrated by the economist Daniel Kahneman, who won a Nobel Prize in Economics for his work in this area). If fear of loss is frightening, the thought of losing everything is terrifying and unthinkable.

In loss, the unfortunate victims have nothing, and feel like they are less than nothing. Indeed, the Midrash, refers to this sentiment in saying that “poverty is like death”. Faced with extreme losses, it feels like life is not worth living; indeed, Job, after suffering the loss of his family and his wealth, is urged by his wife to curse God and commit suicide.

But this is the wrong answer. Even when stripped of everything else, people still have their character. In times of extreme stress, a person still has the courage to cope with their circumstances, and the dignity to transcend their limitations. Although impoverished and homeless, man still holds the keys to his own character.

Character is our most precious possession. Little David, a shepherd boy armed only with a slingshot, can take on Goliath because he has something Goliath lacks: character. David’s weapons are courage and cunning; weapons like these are held in one’s heart, not in one’s hands.

Dreams are another priceless possession that can never be destroyed. No matter what a person’s situation, he can still pursue his dreams. And when the dispossessed pursue their dreams, they can change the world. The Prophet Zachariah describes the messiah as poor, and riding on a simple donkey. Zachariah’s words remind us that if you want to redeem the world, you need to hold on tight to your dreams, even in poverty and hardship.

Throughout history, many have faced the question of “what do you have when you have nothing?”. Some, like Job’s wife, have given the wrong answer, and given up. But those who continue to hold courageously onto their dreams have changed the world.

A few months ago, I visited the Museum of the Jewish Heritage in New York. On display was a special chuppah commissioned in the year 1946 by the Joint Distribution Committee. (a chuppah is a marriage canopy used in Jewish weddings). What made this chuppah unique was that it was for the use of Holocaust survivors who were marrying each other after surviving the war.

When I saw this chuppah, I was overwhelmed with emotion. How is it that people who had seen so much destruction, who had lost everything, could still get married? Isn’t it absurd to try again at life when you have nothing left? But I realized that these couples where not truly destitute and bereft; after all they had their dignity and their dreams, the most important possessions in the world. And it is these couples, with nothing else but each other, who went about rebuilding the Jewish world and succeeding beyond their wildest dreams.

These poor survivors, who had nothing in their hands, actually had everything they needed, tucked away in their hearts.

Natural disasters have dominated the news. In June there were the disastrous floods in the Midwest, and in July, wildfires ravaged Northern California. Thousands have watched their homes and possessions destroyed.

It is particularly painful to consider the fate of those who lived outside of flood or fire “range”, and were not insured. In a matter of hours, they watched the bulk of their assets disappear, along with their homes and communities. In natural disasters like these, lives are ravaged along with the countryside.

The question that nature forces upon the survivors of these catastrophes is simple: what do you have when you have nothing? It's a question that seems absurd at first; if you have lost everything, then you truly have nothing.

Actually, those of us who live comfortably are afraid of contemplating this question. We are driven more by a fear of loss than by any possibility of gain. (This has been demonstrated by the economist Daniel Kahneman, who won a Nobel Prize in Economics for his work in this area). If fear of loss is frightening, the thought of losing everything is terrifying and unthinkable.

In loss, the unfortunate victims have nothing, and feel like they are less than nothing. Indeed, the Midrash, refers to this sentiment in saying that “poverty is like death”. Faced with extreme losses, it feels like life is not worth living; indeed, Job, after suffering the loss of his family and his wealth, is urged by his wife to curse God and commit suicide.

But this is the wrong answer. Even when stripped of everything else, people still have their character. In times of extreme stress, a person still has the courage to cope with their circumstances, and the dignity to transcend their limitations. Although impoverished and homeless, man still holds the keys to his own character.

Character is our most precious possession. Little David, a shepherd boy armed only with a slingshot, can take on Goliath because he has something Goliath lacks: character. David’s weapons are courage and cunning; weapons like these are held in one’s heart, not in one’s hands.

Dreams are another priceless possession that can never be destroyed. No matter what a person’s situation, he can still pursue his dreams. And when the dispossessed pursue their dreams, they can change the world. The Prophet Zachariah describes the messiah as poor, and riding on a simple donkey. Zachariah’s words remind us that if you want to redeem the world, you need to hold on tight to your dreams, even in poverty and hardship.

Throughout history, many have faced the question of “what do you have when you have nothing?”. Some, like Job’s wife, have given the wrong answer, and given up. But those who continue to hold courageously onto their dreams have changed the world.

A few months ago, I visited the Museum of the Jewish Heritage in New York. On display was a special chuppah commissioned in the year 1946 by the Joint Distribution Committee. (a chuppah is a marriage canopy used in Jewish weddings). What made this chuppah unique was that it was for the use of Holocaust survivors who were marrying each other after surviving the war.

When I saw this chuppah, I was overwhelmed with emotion. How is it that people who had seen so much destruction, who had lost everything, could still get married? Isn’t it absurd to try again at life when you have nothing left? But I realized that these couples where not truly destitute and bereft; after all they had their dignity and their dreams, the most important possessions in the world. And it is these couples, with nothing else but each other, who went about rebuilding the Jewish world and succeeding beyond their wildest dreams.

These poor survivors, who had nothing in their hands, actually had everything they needed, tucked away in their hearts.

Thursday, July 03, 2008

What is “Naches”?

It is the great parental quest: to receive joy from one’s children. In Yiddish, the word “naches” (which means parental joy) is laden with emotional connotations, the result of generations of immigrants dreaming of their children’s success.

To many Jews of a certain era, naches was defined by four simple words: “my son the doctor”. This particular parental obsession was often lampooned for going overboard. One joke is about an apocryphal birth announcement that declared “Mr. and Mrs. Irving Goldberg are pleased to announce the birth of their son, Dr. Jeffrey Goldberg.” Jokes aside, the mindset of “my son the doctor” gives a distorted picture of what the parent-child relationship is about.

Pushing a child in order to provide the parent with pride can have destructive consequences. Elisha, a second century Rabbi, is chosen by his father Abuya to become a Rabbi so that Abuya could impress others with his son’s ability. Elisha does become a great Rabbi, but in an era of Roman persecutions, eventually crumbles and becomes a heretic. Unfortunately, Elisha’s studies left his soul empty because they were intended to impress his father. In the end, neither father nor son had any naches.

This uglier side of “getting naches” is what psychologists call “achievement by proxy syndrome”. A parent with simple achievements sees his child, the prodigy, as a ticket to greatness. The parent-child relationship is then reduced to a puppet show, with the child acting as the parent’s puppet, dancing to the tune of the parent’s dreams. In the end, both parent and child lose their souls and insanity ensues.

Achievement by proxy syndrome leads to a multitude of dysfunctions. There are violent altercations between fathers and coaches over the proper treatment for athletic prodigies; there are parents who quit their own careers in order to manage their children’s “talent”. And the child ends up paying dearly for a childhood in a pressure cooker; indeed, Macaulay Culkin and Jennifer Capriati are poster children for the excesses of “achievement by proxy syndrome”.

True naches is not about getting, it’s about giving. The real joy in parenting comes from being a true parent. A parent’s role is to give guidance and impart wisdom to one’s children. When the Bible tells the child “Hear, my son, your father's instruction and do not forsake your mother's teaching”, it is reminding us of the parent’s greatest role, as a teacher.

Randy Pausch is a college professor and father of three young children, who was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in the summer of 2006. After going on permanent leave, he returned to university to deliver one final presentation based on the wisdom he had learned from life experience. This lecture that became a youtube sensation (and later a bestselling book) called “The Last Lecture”. Pausch explains in the forward to the book that the lecture was his way of “bottling” the life lessons he wanted to impart to his children as they grew up.

Pausch’s book is an exercise in true naches; it’s a dying father’s way of giving his children a legacy of authentic wisdom.

Most importantly, naches is about love. Parents transform the lives of their children when they show dedication and devotion to them. And the parents that do this the most are the parents of the developmentally disabled. Unfortunately, they often stand alone in their efforts.

Until recently, a child with cognitive impairments didn’t have a Bar-Bat Mitzvah. Synagogues were too rigid and formal to accommodate the needs of the developmentally disabled. But that is changing. In Boston, a program called “Gateways” has enabled dozens of developmentally disabled children to have their own innovative Bar-Bat Mitzvahs. I myself have been involved in several Bar-Bat Mitzvahs like this, and there is no question that there are powerful emotions in the air. You can sense the love, you can sense the family’s dedication, and as the young man finishes his carefully rehearsed presentation, you can sense something else as well:

Authentic naches.

It is the great parental quest: to receive joy from one’s children. In Yiddish, the word “naches” (which means parental joy) is laden with emotional connotations, the result of generations of immigrants dreaming of their children’s success.

To many Jews of a certain era, naches was defined by four simple words: “my son the doctor”. This particular parental obsession was often lampooned for going overboard. One joke is about an apocryphal birth announcement that declared “Mr. and Mrs. Irving Goldberg are pleased to announce the birth of their son, Dr. Jeffrey Goldberg.” Jokes aside, the mindset of “my son the doctor” gives a distorted picture of what the parent-child relationship is about.

Pushing a child in order to provide the parent with pride can have destructive consequences. Elisha, a second century Rabbi, is chosen by his father Abuya to become a Rabbi so that Abuya could impress others with his son’s ability. Elisha does become a great Rabbi, but in an era of Roman persecutions, eventually crumbles and becomes a heretic. Unfortunately, Elisha’s studies left his soul empty because they were intended to impress his father. In the end, neither father nor son had any naches.

This uglier side of “getting naches” is what psychologists call “achievement by proxy syndrome”. A parent with simple achievements sees his child, the prodigy, as a ticket to greatness. The parent-child relationship is then reduced to a puppet show, with the child acting as the parent’s puppet, dancing to the tune of the parent’s dreams. In the end, both parent and child lose their souls and insanity ensues.

Achievement by proxy syndrome leads to a multitude of dysfunctions. There are violent altercations between fathers and coaches over the proper treatment for athletic prodigies; there are parents who quit their own careers in order to manage their children’s “talent”. And the child ends up paying dearly for a childhood in a pressure cooker; indeed, Macaulay Culkin and Jennifer Capriati are poster children for the excesses of “achievement by proxy syndrome”.

True naches is not about getting, it’s about giving. The real joy in parenting comes from being a true parent. A parent’s role is to give guidance and impart wisdom to one’s children. When the Bible tells the child “Hear, my son, your father's instruction and do not forsake your mother's teaching”, it is reminding us of the parent’s greatest role, as a teacher.

Randy Pausch is a college professor and father of three young children, who was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in the summer of 2006. After going on permanent leave, he returned to university to deliver one final presentation based on the wisdom he had learned from life experience. This lecture that became a youtube sensation (and later a bestselling book) called “The Last Lecture”. Pausch explains in the forward to the book that the lecture was his way of “bottling” the life lessons he wanted to impart to his children as they grew up.

Pausch’s book is an exercise in true naches; it’s a dying father’s way of giving his children a legacy of authentic wisdom.

Most importantly, naches is about love. Parents transform the lives of their children when they show dedication and devotion to them. And the parents that do this the most are the parents of the developmentally disabled. Unfortunately, they often stand alone in their efforts.

Until recently, a child with cognitive impairments didn’t have a Bar-Bat Mitzvah. Synagogues were too rigid and formal to accommodate the needs of the developmentally disabled. But that is changing. In Boston, a program called “Gateways” has enabled dozens of developmentally disabled children to have their own innovative Bar-Bat Mitzvahs. I myself have been involved in several Bar-Bat Mitzvahs like this, and there is no question that there are powerful emotions in the air. You can sense the love, you can sense the family’s dedication, and as the young man finishes his carefully rehearsed presentation, you can sense something else as well:

Authentic naches.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

Article = Combination of Two Posts

This column is the combination of this post and this post. (Due to space limitations, I have to cut each post, leaving out some important stuff, though.)

The Humble Hero

Why be humble? It seems so passé. The word “humility” immediately conjures up the medieval image of a cringing, cloistered clergyman, subsisting on breadcrumbs and brackish water. This sort of self-abnegation seems out of place in the 21st century, where self-promotion and self-indulgence are the norm. Humility can only get in the way of “exercising leadership” or “promoting your personal brand”.

We reject humility out of ignorance. Being humble has nothing to do with being meek, or lacking in self confidence. In fact, humility is the hallmark of any true hero. The humble hero doesn’t aspire to glory, or even humility; he simply wants to do his job. Or, as the Mishnah puts it:

“Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai would say: If you have learned a great deal of Torah, don’t take credit for yourself---it’s for this reason that you were created.”

This Mishnah teaches us that authentic responsibility is not pursued in order to attain glory. The truly humble live to achieve lofty goals, but make little of it; they see themselves simply as doing what is expected of them. Their attitude is that they are “just doing their job”.“I’m just doing my job” is the motto of humble heroes. Their humility is based on a work ethic which drives them to succeed in silence, content to have accomplished what life expected of them.

On May 12th Irena Sendler passed away. During World War II, Irena, a young mother and social worker, was a member of a Polish underground devoted to saving Jews. With great courage and cunning, Irena used her position to smuggle 2,500 children out of the Warsaw ghetto and hide them in orphanages.

Reading the obituaries about Irena, it’s hard not to notice the differences between this humble woman and today’s erstwhile heroes. Our contemporary heroes are celebrities, people who look good on baseball diamonds, on movie screens and on the red carpet. The “entertainment media” breathlessly follows their every move. These celluloid heroes have our undivided attention, and are famous for being famous.

In actuality, a real hero doesn’t look good; they do good. And after they’ve done good, they don’t revel in self congratulation, but rather think about what more they could have done. After receiving a long overdue award from Poland in 2007, Irena declared:

"I could have done more…..this regret will follow me to my death.".

Irena is a genuine hero. Like all humble heroes, she was “just doing her job”. Or, to put it in Irena’s words:

"Every child saved with my help and the help of all the wonderful secret messengers, who today are no longer living, is the justification of my existence on this Earth, and not a title to glory."

I wish the justification for my existence on earth was as good as Irena’s.

This column is the combination of this post and this post. (Due to space limitations, I have to cut each post, leaving out some important stuff, though.)

The Humble Hero

Why be humble? It seems so passé. The word “humility” immediately conjures up the medieval image of a cringing, cloistered clergyman, subsisting on breadcrumbs and brackish water. This sort of self-abnegation seems out of place in the 21st century, where self-promotion and self-indulgence are the norm. Humility can only get in the way of “exercising leadership” or “promoting your personal brand”.

We reject humility out of ignorance. Being humble has nothing to do with being meek, or lacking in self confidence. In fact, humility is the hallmark of any true hero. The humble hero doesn’t aspire to glory, or even humility; he simply wants to do his job. Or, as the Mishnah puts it:

“Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai would say: If you have learned a great deal of Torah, don’t take credit for yourself---it’s for this reason that you were created.”

This Mishnah teaches us that authentic responsibility is not pursued in order to attain glory. The truly humble live to achieve lofty goals, but make little of it; they see themselves simply as doing what is expected of them. Their attitude is that they are “just doing their job”.“I’m just doing my job” is the motto of humble heroes. Their humility is based on a work ethic which drives them to succeed in silence, content to have accomplished what life expected of them.

On May 12th Irena Sendler passed away. During World War II, Irena, a young mother and social worker, was a member of a Polish underground devoted to saving Jews. With great courage and cunning, Irena used her position to smuggle 2,500 children out of the Warsaw ghetto and hide them in orphanages.

Reading the obituaries about Irena, it’s hard not to notice the differences between this humble woman and today’s erstwhile heroes. Our contemporary heroes are celebrities, people who look good on baseball diamonds, on movie screens and on the red carpet. The “entertainment media” breathlessly follows their every move. These celluloid heroes have our undivided attention, and are famous for being famous.

In actuality, a real hero doesn’t look good; they do good. And after they’ve done good, they don’t revel in self congratulation, but rather think about what more they could have done. After receiving a long overdue award from Poland in 2007, Irena declared:

"I could have done more…..this regret will follow me to my death.".

Irena is a genuine hero. Like all humble heroes, she was “just doing her job”. Or, to put it in Irena’s words:

"Every child saved with my help and the help of all the wonderful secret messengers, who today are no longer living, is the justification of my existence on this Earth, and not a title to glory."

I wish the justification for my existence on earth was as good as Irena’s.

Thursday, May 22, 2008

The Survivors vs. Hitler

In a recent article in Newsweek’s My Turn, Shirley Paryzer Levy writes about her late father:

"When my father felt the end was near, he started to obsess about his past. He decided that if he didn't start talking about the Holocaust, who would remember? He made a series of audiotapes beginning with his life in Europe, leading up to the Holocaust and ending with his wedding to my mother in Germany in 1946……